« Post-Empire attained the mainstream in 2010 and 2011 with Cee Lo Green’s “Fuck You” gleefully providing the soundtrack and examples began flourishing everywhere. The Kardashians understood it, as did MTV’s Jersey Shore’s participants and audience. We saw it when Lady Gaga arrived at the Grammys that year sealed in an egg and stared down Anderson Cooper in a 60 Minutes segment, admitting she liked to smoke weed when writing songs and basically daring him, “What are you going to do about that, bitch?” Nicki Minaj grasped it when she assumed one of her various bizarre alter-egos on the red carpet, and yet Christina Aguilera didn’t get it at all when starring in Burlesque, while continuing to ape Empire attitudes by idolizing and glamorizing herself unironically. Ricky Gervais, freewheeling and insulting as he hosted the Golden Globes in January 2011, understood, while Robert Downey Jr., getting passive-aggressively pissed-off at Gervais during the same show, didn’t seem to, and Robert De Niro, subtly ridiculing his career while accepting his lifetime achievement award, generally understood it as well—though later, in lamely attacking Trump, he seemed like an unhinged old-school poser.

John Mayer at one point looked like he was going to be the original post-Empire poster boy for his TMZ appearances (he was the first celebrity to realize what a game changer TMZ would be) and also provided a key example of post-Empire in his racially and sexually charged Playboy interview in 2010, until he apologized for it. Kanye West scored a major post-Empire moment with his interruption of Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech at the 2009 Video Music Awards, as well as with his masterpiece post-Empire single “Runaway”—whereas Bruno Mars or Bono, not so much. James Franco, hosting that year’s Oscar telecast without taking it seriously, treating it with gentle disrespect, gave another instance of post-Empire performance, while his peppy and earnest cohost, Anne Hathaway, didn’t appear to have a clue. Post-Empire was Mark Zuckerberg staring with blank impatience at Leslie Stahl on 60 Minutes when telling her how The Social Network got its genesis story totally wrong—by suggesting he’d created Facebook because he was rejected by a bitchy girl—and that this conceit had been dreamt up by the Empire screenwriter Aaron Sorkin. For every outspoken I-don’t-give-a-fuck Empire celebrity—whether Muhammad Ali or Gore Vidal or Bob Dylan or John Lennon or even Joni Mitchell—there were always dozens like Madonna, a true queen of Empire, who never seemed real or funny, everything about her looking, in retrospect, dreadfully earnest and manufactured, or Michael Jackson, the ultimate victim of Empire celebrity, a tortured boy lover and drug addict who humorlessly denied he was either. Keith Richards, in his 2010 memoir Life, was a rare example of a healthy, post-Empire geezer transparency, and for my younger friends this kind of transparency was increasingly the norm: What did shame mean anymore?

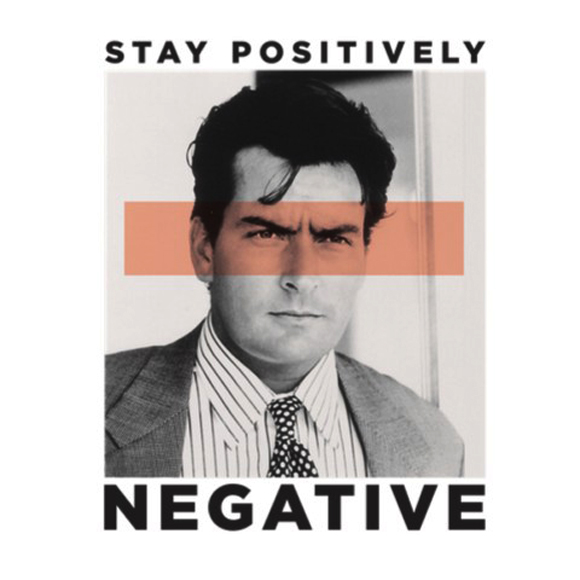

In 2011, post-Empire wasn’t just about publicly admitting doing “illicit” things and coming clean; it was a then-radical attitude that claimed the Empire lie no longer existed—realness, transparency, and the tactility of your flesh were the only qualities that mattered. To the former gatekeepers, someone like Charlie Sheen seemed dangerous and in need of help because he was destroying illusions about the nature of Empire celebrity—as did Trump five years later. Sheen had long been a role model for a certain kind of male fantasy, a degrading one, perhaps, but isn’t that true of most male fantasies? (I never knew any straight men who fantasized about Tom Cruise’s personal life.) Sheen had always been a bad boy, which was part of his appeal for men and women, and this was what Chuck Lorre, the co-creator of Two and a Half Men, initially responded to—a manly mock dignity that both sexes liked a lot. What Sheen exemplified and clarified was that not giving a fuck about what the public thinks about you or your personal life is actually what matters the most, that the public will respond to you even more fervently, because you’re free and that’s exactly what they all desire—everyone, that is, except for the network or the show’s creator or the corporation that has made you so fabulously wealthy. »

White, Breat Easton Ellis, 2019.

DERNIERS COMMENTAIRES