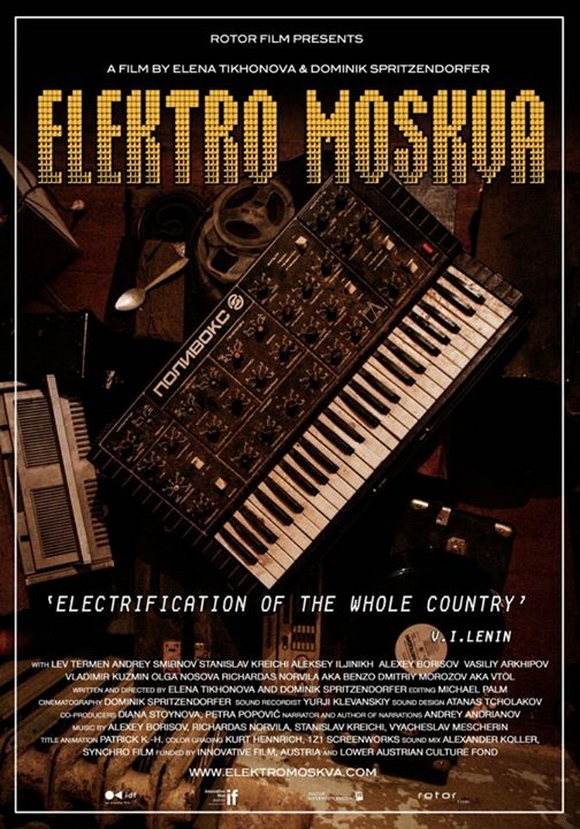

Il y a presque un siècle naissait l’étérophone, autrement appelé Thérémine, du nom de l’ingénieur russe qui le conçu. Ce curieux objet qui se jouait sans le toucher, grâce à un champ électro-magnétique, fut le premier instrument de musique électronique. Dans les années 60, Robert Moog commercialisera le concept, après la tentative échouée du soviétique, et le synthétiseur deviendra un instrument pop parmi d’autres. C’est l’histoire du « Synthé chez les Soviets » qu’ont choisi de raconter Dominik Spritzendorfer et Elena Tikhonova dans leur documentaire « Elektro Moskva« .

L’histoire de l’électrification de l’URSS, transformée en véritable laboratoire peuplé d’usines et de villes nouvelles, la conquête spatiale, la défense et l’effervescence scientifique, puis la période de déconstruction et l’amoncellement d’outils, gadgets et appareils électroniques devenus inutiles ou dépassés. Un voyage cosmique qui emprunte les lignes de chemin de fer, les routes, se rend dans des fabriques désaffectées, des terrains vagues transformés en brocantes, des centre-villes, des studios de fortune, … partout où le règne de l’électronique a fait des adeptes, qu’ils soient collectionneurs, chercheurs, réparateurs, musiciens noise ou simples témoins. A l’image de cet ancien s’étant fabriqué une antenne de télé avec des fourchettes (la télé existait oui, mais pas les antennes !), le mot d’ordre de ces années de créativité fertile fut le suivant : « rien ne marche, mais tu dois en tirer le meilleur ! ».

ENGLISH VERSION

Answers by Director: Dominik Spritzendorfer

How did you two meet ? Who got the idea of this documentary ?

Elena and I met back in 1997 as students of Moscow film institute VGIK. I have been living in Russia for 3 years, in 2000 we both moved to Vienna to live and work as filmmakers. Lena did some rather experimental short movies, I was always more into documentary. The idea came up, when we met Richardas Norvila aka Benzo, an electronic musician, philosopher and psychiatrist from Lithuania, who lives in Moscow and makes sound with old soviet synthesizers and other gear. He has his own philosophy about those instruments and loves their imperfection, which he claims to be due to the deficiency of russian life itself. We got curious and started to dig deeper into the story of those instruments and their origin. And we found a lot of stories that combined to a unique narration about how it felt to be creative in the totalitarian soviet system and how this history is influencing contemporary musicians in Russia today.

Speak me a bit about the conception of the movie. How much time did you spend touring Russia ?

We made this film during a period of 8 years! It was not easy to find fundings for such an ‘exotic’ story but due to our passion and persistency we got a budget to cover the costs, produced by ourselves. We just believed in it and wanted to make this film happen. Over the years we did a lot of research, finding out more and more the story grew over the years, with some sensational discoveries from both state and private archives. Finally we had 2 shooting periods in Russia, both around a month long.

Form the beginning on, we wanted to make it a documentary with a fairy-tale-like atmosphere, with a very subjective point of view, which reflects the inner state of a person remembering history and commenting on it in a humorous, even cynical way. that is a very typical russian manner.

« Come what may, for something will come anyway. There was never a time when there was nothing!” is a saying from soviet times, which tells a lot about what is expected of the future to come. We have that in the film.

Are Soviets the originators of electronic music ?

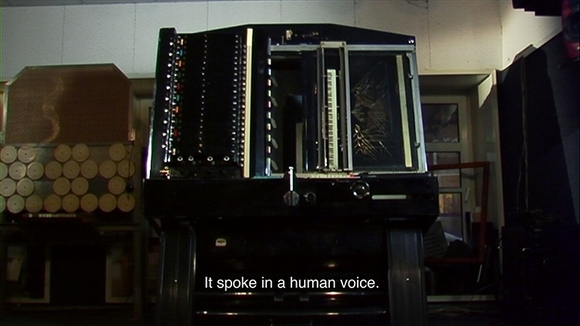

When Leon Theremin invented the Theremin in 1919 he was a pioneer in electronic music. His colleagues in the institute were joking: ‘Theremin plays Gluck on a Voltmeter.’ His instrument was completely outta space for that time. Of course, there were other inventions in this field in western Europe and America, too, but I dare to call Theremin the godfather of electronic music. Though he spent most of his life as scientific prisoner, being forced to invent for soviet secret intelligence and warfare. no music there.

Is there a lot of Theremin left today ? Do you personnally know how to play ?

In the 20ies, the Theremin was expected to become THE instrument of the future and soon be found in every household. This never happened. Known mainly from soundtracks of horror movies, it is still a rather exotic, strange gimmick instrument, but it still is magic.

There is the Theremin-Centre in Moscow led by Andrey Smirnov, which houses a huge archive of texts and instruments, there are lectures and courses on electronic music and playing the Theremin. It is a meeting point for a young generation of music makers, too.

I tried to play it there and I own a little diy theremin from Japan, but it’s rather playing around with it, not seriously.

Did Robert Moog 1961’s invention stole the Theremin concept ?

He didn’t steal it, he built licensed theremins for the american market, modified it with the time. Moog was a big admirer of Theremin.

Leon Theremin had an extraordinary existence. He lived the 1917 revolution and soon after created an instrument every western pop icon of the century used, then he went to the US to assure and sell the product to RCA, and suddenly came back in USSR to end up working into goulag laboratories. What a journey !

It is an amazing life he had, so much linked to the madness of the 20th century, the soviet experiment, the electronic revolution, the cold war etc. besides the film by Steven Martin there is a biography by Albert Glinsky on Theremins life.

For Elektro Moskva we used footage from Theremins last interview where he was 97 years old, talking about his inventions and work for the KGB. This footage was stored underneath the filmmakers bed for 20 years and has never been seen before.

By the way, this November it will be 20 years since Theremins death. At high age, he used to mention that he might live forever since his name spelled backwards was NIMEREHT, which means ‘never dies’ in russian.

Paradoxally, these periods seemed more creatively free than today’s electronic music under the control of drum machines and synthesizers. So, what went on since the last 100 years ?

Hard to say. In soviet times, there was a strict control of everything. If musicians were not published on the one and only state record label ‘Melodija’, there were not published at all. Only exception was music for films (Tarkovsky ‘s composer Edward Artemjev used the once of a kind ANS synthesizer for his films) and especially animated films.

Everything else including western music was underground, copied from tape to tape of what was sneaking through the iron curtain. So there were a lot of dreams about the ‘other’ side of the curtain associated to modern electronic music. It was mostly a reflection and imitation of what was going on in the West, with a lag of some years.

Today, electronic music is such a global phenomenon, that it is actually impossible to mark local specifics. But there still IS great music made today! it only has to be found in the ocean of 99% of crap.

Could we say, with a bit of provocation, Iron Curtain, at some point, postponed the uniformisation of music, and culture ?

Everything unique that happened there was DESPITE of the circumstances, not thanks to them. Rather like a resistant flower growing out of a crack in a rock.

On the other side some kind of soviet easy listening was used by the regime to pamper the people and make them forget their problems. Number 1 was Mesherin’s Orchestra of electronic instruments, they were aired through TV and radio around the clock. the soviet muzak of the 60ies!

How communist authorities managed to control the proliferation of these ‘electronic gagdets’ ? Lenin helped to popularize the Theremin at first, but after ?

Lenin was never really interested in the instrument, though much more in it’s and Theremins more practical qualities: the instrument is actually a motion detector, perfect to be used for surveillance and control, and Theremin was good for the role of spying scientific innovations abroad.

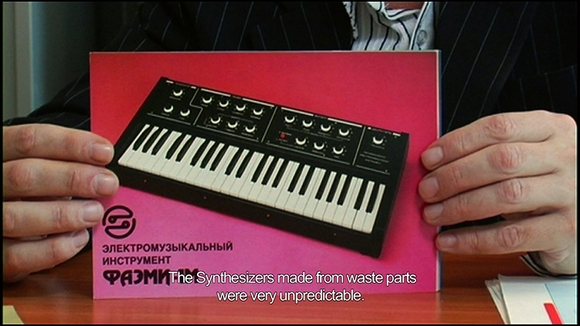

Electr. instruments were never about to be widely popular, even in the 80ies, when there was mass production of synthesizers, there was no structure to obtain them.

What are the most incredible meetings you made during the shooting ?

Meeting with Vladimir Kuzmin, the inventor of the Polyvox and a lot of other synthesizers, in Ekaterinburg was a great experience. But strangely, he was still very reserved about details of the synthesizer production within military facilities since he committed to maintain silence about these ‘military secrets’ back in the 80ies. That he still fears consequences if he talked is a little absurd. It was not easy to get some information out of him, which was useful for the film.

Another adventure was shooting in sensitive locations in Moscow,eg. we shot a scene near a power plant with Benzo, after that our soundguy Yuri was detained by securities while recording some sound of the plant. For 2 hours the securities tried to get a clue out of the recordings.

Is questionning electronic devices collectors get boring after some time ? How did you manage to keep your research exciting ? And to preserve it from nostalgia ?

We tried hard NOT to make a movie that is only interesting for the hardcore electronic music nerd community. Neither we are. We wanted to tell a story about living, inventing and being creative in a totalitarian system, using the music and these awkward instruments as a tool to tell this story.

Probably this film might be received as nostalgic, however we wanted to get beyond that. We are not saying: it was all better then. Of course it was a hard life that people from the west cannot even imagine. But we want to draw attention to this kind of creativity that you need, when you cannot walk into a store and just buy whatever you need, but have to use your brains to get what you want, how you make it. in our abundant society we loose those abilities. That’s not nostalgia.

DERNIERS COMMENTAIRES